Understanding What To Settle

We know the difference between rolls, as we can look at the graph of the roll distribution. But what’s the difference between the 5 different resources? This is a lot harder to figure out, since we don’t have a nice graph charting what is most important. We can look at what we use the resources for, and the value of those things though. We know that there are only 4 different things to spend our resources on (or 5 if we’re playing Seafarers):

- Roads (or Ships)

- Settlements

- Cities

- Development Cards

Settlements: The most settlements that can possibly be built by a single player in Settlers is 5 – upgrading the original 2 settlements to cities and building 5 settlements gives 9 points, and no more settlements before a city us built, in which case 10 points is reached. So, for settlement building, the most that we need is:

5 wood, 5 brick, 5 sheep, 5 wheat.

Roads: I left roads until after the settlements for a reason – the main purpose of road building is to develop settlements. So, when we find the maximum number of settlements bought, we can estimate the amount of road needed for the task. With 5 settlements being our maximum number, we have 9 roads bought, assuming we connect them all to one of our original settlements, and all settlements are spaced 2 spaces apart. Now, let’s say that we had to space of 3 roads twice in our route. Anyone who has played the game knows that this setup is a more inefficient way of building, but this will give us an upper limit on our spending. Now we have 11 roads. This is also sure to give us the longest road in most games played. So, our maximum spending on roads is:

11 wood, 11 brick.

Ships: When playing the Seafarers expansion pack, we can say that we split our road building into ships and roads. Also, since we play to more than 10 points (sometimes), we can add extra roads or ships to our route, as to build more settlements. 20 is the highest upper limit on roads and ships that I can justify. This means that our spending would look like this:

20 wood, 10 brick, 10 sheep.

Cities: The most cities that can possibly be built in a game are 4 – each player is only provided with 4 cities. So for city building, the most that we need is:

8 wheat, 12 ore.

Development Cards: This is where we run into a bit of a snag. Technically, you could buy all of the development cards and not win. This is obviously not a great strategy. I proposed the idea of buying 4 development cards per game but this is up to each person. Because there is about a 50% chance of drawing a knight, the largest army costs about 6 development cards. Out of the 3 cards that were bought that were not knights, there is an average of about 1.5 victory points. This is probably the most anyone can hope for out of the development cards on a consistent basis. So, we have 6 development cards at most (sort of), costing us:

6 sheep, 6 wheat, 6ore.

Ok, now, let’s total them up. At maximum capacity for all spending, our resource distribution would look like this:

- Settlers: 16 wood, 16 brick, 11 sheep, 19 wheat, 18 ore

- Seafarers: 25 wood, 15 brick, 21 sheep, 19 wheat, 18 ore

This is obviously an extremely poor estimate. For example, on average, a winner has 2.3-2.8 cities built per game – significantly less than the 4 maximum. Also, road building has a lot of possibility of decreasing. So, while this analysis gives a decent estimate of the worth of commodities, I believe that the statistics provide a more solid source of data.

I am going to look at a set of graphs that should provide a better insight to the worth of resources.

Settlement (Resource) Development

There are two types of settlement development: the initial placing of settlements, and the buying of subsequent settlements throughout the game. Starting Resources notes the resources that settlements are placed on initially. The graph shows us what resources winners tend to start on. It seems that wheat and wood are most popular among starting resources, with brick being the least popular, followed shortly by ore. Keep in mind that in a regular game of Settlers, there are only 3 brick and ore hexes, while there are 4 of the others. So, using the weights of distribution (3 and 4), we can find the value of starting on each resource:

There are two types of settlement development: the initial placing of settlements, and the buying of subsequent settlements throughout the game. Starting Resources notes the resources that settlements are placed on initially. The graph shows us what resources winners tend to start on. It seems that wheat and wood are most popular among starting resources, with brick being the least popular, followed shortly by ore. Keep in mind that in a regular game of Settlers, there are only 3 brick and ore hexes, while there are 4 of the others. So, using the weights of distribution (3 and 4), we can find the value of starting on each resource:

Brick = 0.3000

Wood = 0.3075

Sheep = 0.2925

Wheat = 0.3675

Ore = 0.3233

Wheat and ore seem to be most important, while brick and sheep are least important.

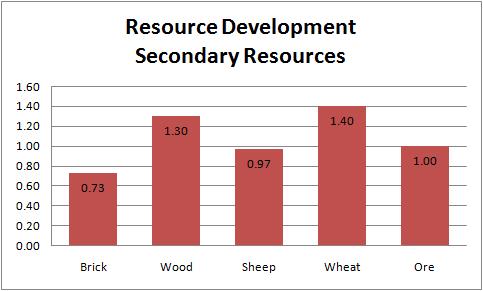

Secondary Resources shows the distribution of where settlements are built after the game has started. We can use the same distribution of resources to find value of these secondary resources as well:

Secondary Resources shows the distribution of where settlements are built after the game has started. We can use the same distribution of resources to find value of these secondary resources as well:

Brick = 0.2600

Wood = 0.3250

Sheep = 0.2425

Wheat = 0.3500

Ore = 0.3333

Again, wheat is most important, this time by less, as wood and ore increase in value as the game goes on. Sheep decrease in value, as does brick.

Our final analysis comes by looking at City Development, which is the resources that we upgrade to cities. Using the weights that have been used previously, we can see the change in value:

Our final analysis comes by looking at City Development, which is the resources that we upgrade to cities. Using the weights that have been used previously, we can see the change in value:

Brick = 0.3233

Wood = 0.2675

Sheep = 0.3325

Wheat = 0.4750

Ore = 0.4567

Here we see wheat and ore extremely valuable, as the other resources pale in comparison. Using these values, we can map the value of each resource as the game plays out.

Brick = 0.3000 – 0.2600 – 0.3233 (average of 0.2944)

Wood = 0.3075 – 0.3250 – 0.2675 (average of 0.3000)

Sheep = 0.2925 – 0.2425 – 0.3325 (average of 0.2892)

Wheat = 0.3675 – 0.3500 – 0.4750 (average of 0.3975)

Ore = 0.3233 – 0.3333 – 0.4567 (average of 0.3711)

Overall, the order of importance throughout the game is wheat, ore, wood, brick, and sheep.

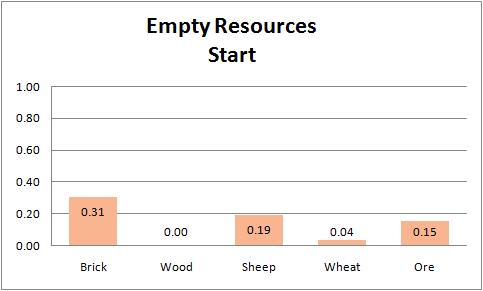

Empty Resources

Negative worth is also an idea that can be looked at. This brings into focus the idea of Empty Resources, which are resources that are not available to the player. For this case, we need to consider scarcity of distribution again, as the more scarce resources are more likely to not be available.

Brick = 0.1033

Wood = 0.0000

Sheep = 0.0475

Wheat = 0.0100

Ore = 0.0500

Brick seems to be the most useless, as not starting on it seems to not affect winners results by as much as the other resources.

Looking at the resources that were not taken advantage of throughout the whole game also gives a good estimate of the uselessness of each resource.

Looking at the resources that were not taken advantage of throughout the whole game also gives a good estimate of the uselessness of each resource.

Brick = 0.0500

Wood = 0.0000

Sheep = 0.0100

Wheat = 0.0000

Ore = 0.0100

So we have a mapping of the uselessness of each resource throughout the game, similar to the utility of each resource throughout the game.

Brick = 0.1033 – 0.0500 (average of 0.0765)

Wood = 0.0000 – 0.0000 (average of 0.0000)

Sheep = 0.0475 – 0.0100 (average of 0.0288)

Wheat = 0.0100 – 0.0000 (average of 0.0050)

Ore = 0.0500 – 0.0100 (average of 0.0300)

So, we can rank resources by uselessness, where brick is the most useless, ore and sheep are close, and finally wheat and wood.

Finally, combining the utility and uselessness of each resource compared to other resources can give us a way to rank resources by order of importance:

Finally, combining the utility and uselessness of each resource compared to other resources can give us a way to rank resources by order of importance:

- Wheat

- Wood

- Ore

- Sheep

- Brick

I have absolutely no data to back this up, but anecdotally, I think sheep and ore would trade places in Seafarers. (We play Seafarers with C&K). If we didn’t have the C&K going simultaneously, I think sheep would be either 1 or 2 in importance.

Sheep most definitely gain value with the added ships, but I’m hesitant to say that they overtake ore completely. Maybe I should look into this more, and come back with more data!

Also, I have somehow managed to play Settlers of Catan for 4 years without ever learning Cities and Knights. I’m planning on trying it soon though!

In economics terms, wood and brick are perfect compliments-you can never use one without the other. Hence, as the price of wood goes up, the price of brick falls (and vice versa).

Now given that there are only 3 brick tiles verses 4 woods, you would expect that brick would be the expensive resource, which would drive down the demand for wood. But your data suggests the opposite. Why is that? Do players oversettle on brick?

I’ve thought about this a lot actually. My best bet is to say that the extra wood tile actually moves to increase its numeric value. This isn’t a value that is fixed throughout the game, as supply and demand influence a resource’s value a lot. But, when you want to line up all of the resources, and say that on average, throughout the span of the game, this is where players move. Does it have some part to do with there being an extra tile, giving more spaces to settle? Sure, maybe. Also, there are more boundaries on 4 wood tiles than 3 brick tiles, so maybe it’s the bordering resources that are driving up value. That’s all legitimate, and I don’t believe it takes away from this quantitative value system I have set up.

Strictly speaking, this is about the people who win, and where they chose to settle and move throughout the game, and it seems that winners would rather punt brick than wood.

I think the reason for the discrepancy in your figures consists in the fact that brick is more scarce than wood, not necessarily more “worthless”. Thus, it is true games are often won without brick and rarely won without wood. But this does not necessarily mean that it is less valuable, just that it is harder to obtain. For example, If I am playing a game and I am setting out to place my initial settlements I will try to get as many valuable numbers as possible, and be short as few resources as possible. The odds are that I will have an easier time finding a good number on wood than brick. If this is the case I will probably pass on the brick and take the wood, hoping to trade for/rob etc in order to get the brick later, something I should not have too much trouble doing since I will most likely have wood from my good resource. In conclusion, a gamer can usually do without brick or wood and since it is usually easier to procure a good wood than a good brick he will most often try to make due without the brick. This does not mean that brick is more useless, just that it is more scarce.

Hi Philip. I think you’re partly right, but I also think there’s some other reasons that stem from it. Take a look at my post on the “Brick-Wood Paradox” and comment there to keep the discussion rolling!

very cool idea although i believe the findings to be too narrowly applied to actually be correct.

the externalities of the game are what make it from being completely solvable. the largest army provides utility through the robber function and not being robbed (besides the random card given-which isnt even that random if you are card counting-the value of not being robbed as much is hard to quantify), the longest road also provides value in establishing locations to build settlements as well as preventing others from building settlements.

both of these however suffer in that they do not implicitly produce resources (other than the one robber card from a knight) like settlements and cities do. each settlement has a compounding effect on your resource income as it allows you a greater resource rate which in turn allows a greater resource rate etc..

the point about glorified trade is off in my opinion. while it is true that the three green cards (monopoly, year of plenty, and roadbuilding) are not always effective that is because they are far more situational but used properly are incredibly effective. even if your posit that it was a glorified trade was true, that would be implying that trades did not have a positive value. in this game due to the integral character of the resources trading can benefit both sides (obviously, thats why trades happen) in a trade with the bank for an ore, wool, and wheat, you can arrive at two cards that might be out of your reach or the ability to steal many more cards through monopoly. these are hardly nonadvantageous.

the effictiveness in quanitfying the resource value is just that, the game is highly situational. each games have different scarcities and surpluses that define the market in a way that an average of the importances of the resources cannot accurately shed any light on. just because wheat is the most important generally does not mean one should give it extra value in a game where it is not scarce.

measuring the average importance of each resource is a bit like measuring the value of gasoline to the average american. a texan might depend on gasoline to travel many miles to work or the grocery store while a new yorker might not even own a car with which to consume gasoline. it is hardly illustrative of the actual truth.

even within a game, certain streaks of numbers can make certain resources flush for a few turns while being scarce for the rest of the game. the market accomodates that and reacts accordingly.

my final point is perhaps the biggest: your assumption that you need x settlements and y cities and z roads etc is flawed. the standard game is to 10 which means one needs some combinations of VPs to reach 10 to win. some wins are four cities and two settlements, some are four settlements, largest army and 4 VP cards. this is to say that there are different strategies with which to play the game based on the position of the board you were given. the most commong split is between the wood/brick strategy and the wheat/ore. most players do not value sheep enough to make it an integral part of the strategy.

the wood/brick strategy is to expand quickly and build settlements, and slowly upgrade to cities with new settlements on ore and wheat. the longest road is part of this strategy. the ore/wheat strategy focuses on vertical expansion into cities and development cards. VP cards and largest army are part of this strategy.

best of luck. i hope you are still playing and learning.

There’s no easy way to do this, which is why the author had to make assumptions. Without assumptions (which, obviously, will not be applicable in every case) it’s impossible to even start an analysis with a game this complex. The article is clearly meant as an obvservational guide and he never claims it as an automatic path to victory.

Best of luck, Cavalcanti. I hope you are still grappling with simple game theory and are still learning.